In this post, I will be critiquing the objection that Sola Scriptura from an epistemological standpoint is not circular. This objection comes from Canonical Theology The Biblical Canon, Sola Scriptura and Theological Method from John C. Peckham.

Is sola Scriptura, then, a product of circular reasoning? To be sure, the one who advocates sola Scriptura has already come to a decision of faith in Scripture. However, it is widely recognized that every epistemological starting point requires a decision to believe in something. It is crucial to recognize, then, that the charge of circularity is not a problem for canonical sola Scriptura specifically but a universal epistemological issue. The one who claims that tradition is needed to get beyond the circularity of canonical sola Scriptura merely adds another epistemological circle, since tradition itself would require some ground for its acceptance. However, it appears that any basis or authority that might be appealed to in order to ground tradition could also be appealed to in order to ground Scripture directly. Ultimately, however, canonical sola Scriptura proclaims that the canon is self authenticating (cf. John 17:17) while at the same time recognizes the appropriateness of taking into account the wider evidence in favor of Scripture. Accordingly, there is no logical fallacy in choosing to accept Scripture’s own claims and thus adopting Scripture as the basis of theology.

Peckham. (2016). Canonical theology. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Response

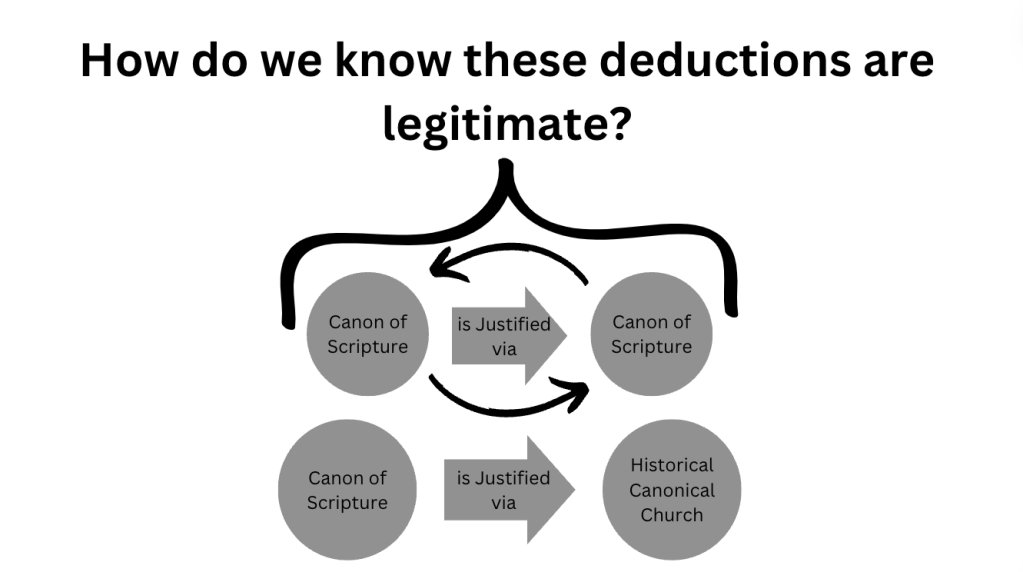

The first problem with this critique is a Category Error since John Peckham is arguing that offering tradition as epistemic criteria is circular because in order to accept tradition requires some first order presupposition for its acceptance. What Peckham is confusing in epistemology is the question of epistemic justification for the use of the Canon vs epistemic justification for legit inferences and deductions via Empiricism. Even though these questions are related, they are distinct.

The question on Canon is asking the epistemic criteria for the use and intelligibility of the Canon of Scripture, not justification for the use of foundational starting points that are used in order to accept inferences and deductions via Empiricism. Peckham is falsely combining these two questions in epistemology–and is a self-refuting argument/critique. Since Peckham accepting sola Scriptura will require unjustified, presupposed starting points in order to accept the revelation of Scripture (i.e. the critique he just gave to Tradition!).

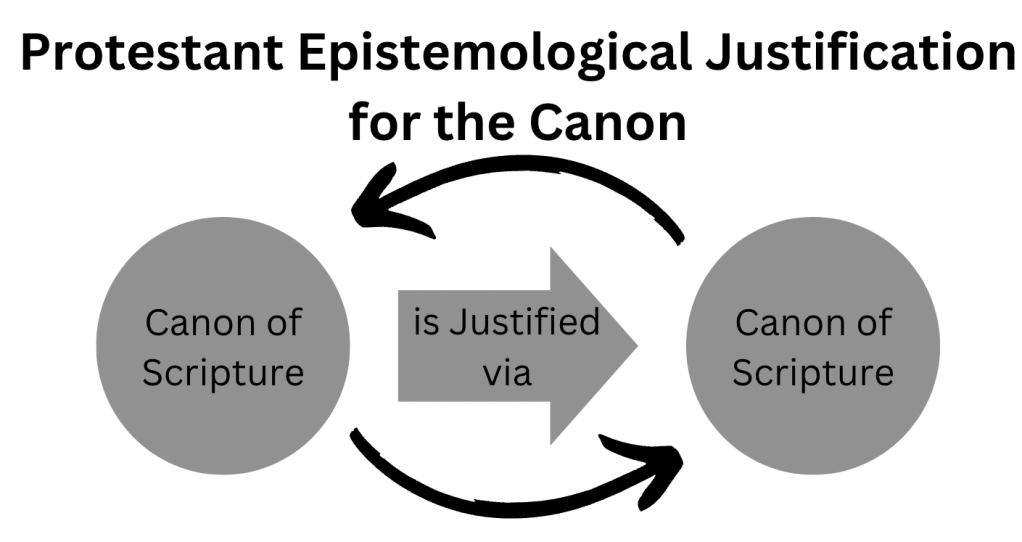

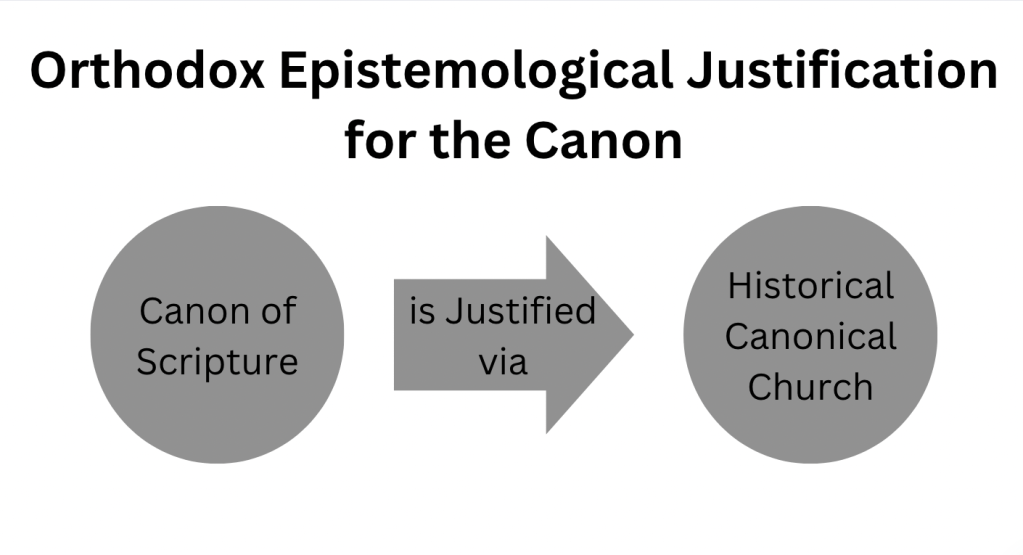

Sola Scriptura will refer to Scripture itself (question begging the 66 book Protestant Canon) in order to justify and provide intelligibility of the Canon of Scripture. This is not epistemic criteria, rather just stating the position of said Protestant. However, the argument for Sacred Tradition justifies its use and intelligibility of the Canon of Scripture by providing a Historical, Canonical Church. That through History, came to the agreement to decree and bind Christendom to a particular Canon of Scripture via the preservation of the church via the Holy Spirit. This is not circular, since justification has been given for why certain books should be within the Canon of Scripture.

Another question in epistemology is asked in order to provide justification for the epistemological deduction of the said Protestant or Orthodox. This is a separate question from justification of the Canon of Scripture. Which is confused by Peckham on his critique of Sacred Tradition.

Analogy

The analogy that can be used in order to understand the epistemic problem of Sola Scriptura is the analogy of Lemonade. Suppose person A and person B has a cup of Lemonade, person B asks person A “How did you get that Lemonade?”. Person A responds “Well, since I have this cup of Lemonade, I’ve examined the content of the Lemonade therefore Lemonade!” Person A’s epistemic justification for their Lemonade is fallacious, since Person A used said Lemonade to justify tangibility of their Lemonade.

Suppose person A asks person B “How did you get that Lemonade?”. Person B responds “I got my Lemonade from the store down the street”. Person B’s response accurately provided epistemic justification for said Lemonade.

However, in order to justify the epistemic deductions of both Person A and B will require another question in epistemology. Even though these questions are related, they are not identical.

Problems with Classic Foundationalism

Peckham also critiques the objection that “sola Scriptura is committed to a Classical Foundationalist epistemological framework”. He argues that sola Scriptura does not subscribe to a Classical Foundationalist framework for epistemology. I will demonstrate how sola Scriptura does submit to a circular, fallacious Classical Foundationalist epistemology.

Some might worry that recognizing the canon as the rule of faith itself rests on a failed foundationalist epistemology. But while communitarian approaches rightly recognize the demise of classical or strong foundationalism, it does not follow from this that one should not posit any kind of theological foundation. In this regard, Franke’s contention that the question — “which has priority, Scripture or the church?” — is “ultimately unhelpful in that it rests on foundationalist understandings,” appears to result from confusion regarding the meaning of “foundationalist”. As Grenz himself notes, “nearly every thinker is in some sense a foundationalist,” at least in the broad sense of recognizing and operating on “the seemingly obvious observation that not all beliefs (or assertions) are on the same level ; some beliefs (or assertions) anchor others (or assertions) that are more ‘basic’ or ‘foundational.‘” In other words, posting something upon which another point or body of knowledge rests does not require adherence to classical/modernistic foundationalism. Accordingly, to classical or strong foundationalism and, indeed, does not require commitment to any particular theory of epistemic justification.

The point here is not to argue from any particular contemporary, all of which will likely either be rejected or significantly improved in the future, but to highlight that adopting the canon as foundational does not require naive commitment to an already defeated concept of classical or strong foundationalism.

Peckham. (2016). Canonical theology. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

As Peckham has rightly pointed out, for all thinkers making epistemic deductions have some type of a priori foundational commitments in epistemology. However, the critique against Protestants on the Canon is not about a priori foundational commitments. It is the fallacious commitment to Classical Foundationalism. The epistemic framework that explains that there is a neutral (or theory-independant) starting points in which individuals can derive facts, evidence–etc. This is show evident where Protestants will presuppose that “the Bible interprets itself” or tota Scriptura. Its attempt to nullify the need of interpretative lenses on Scripture by epistemically commiting to self evident truth is in itself self-refuting. Since proposing that the Scripture is self evident is to presuppose that all Scripture is self evident (i.e. this presupposition is not a ‘neutral’ starting point).

As Father Decon Ananias points out the critique of Coherentism vs Classical Foundationalism;

“The error here, which the coherentist rightly points out, is to think that evidence, statements, meanings, and facts are all theory-independent and can be universally approached in a neutral manner, that is that there is neutral common ground whereby we can derive facts and theories, construct arguments, etc. It becomes clear, upon reflection, that what constitutes as evidence or facts will differ according to one’s own presuppositional commitments and determined by particular epistemic/theoretical paradigms. For example, the word “love” means something entirely different to the Orthodox Christian as opposed to the secularist who has a fundamentally different paradigm. Evidence will look very different to an atheist compared to a theist. These points echoe the thoughts of Wilfrid Sellars who argued that despite receiving the same sense data, all seeing will be a seeing as, a seeing according to a concept[xxxv] or the web of one’s own beliefs and theoretical commitments.”

Ananias, D. (2021, December 25). An Orthodox Theory of Knowledge: the epistemological and apologetic methods of the Church fathers. Patristic Faith. https://www.patristicfaith.com/senior-contributors/an-orthodox-theory-of-knowledge-the-epistemological-and-apologetic-methods-of-the-church-fathers/

Classical Foundationalism breaks down in epistemology by failing to recognize that facts, data, etc is paradigm dependant. All seeing, observing, and reading is performed by a preconceived lens based on various presuppositions. Thus, the Protestant idea that there is a neutral starting point in which all Protestants can derive facts from Scripture is proven false. This fallacious precommitment of self-evident truth is required in order to hold the view of Sola Scriptura.